Esta entrada también está disponible en: Spanish

An infrared camera reveals severe and toxic air contamination at numerous oil and gas sites in Argentina

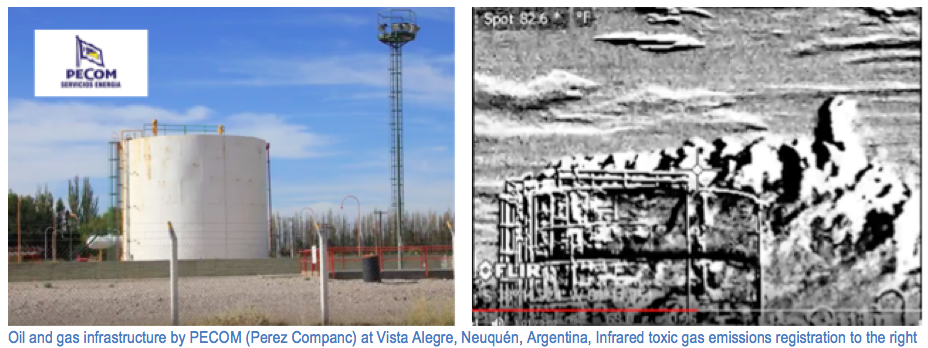

A group of technical experts with cutting edge infrared technology that registers toxic emissions from industrial sites visited Argentina recently, touring key oil and gas extraction and production sites, and registered alarming levels of toxicity. Members of the organization Earthworks and the Center for Human Rights and Environment were invited by Argentina’s Mapuche Indigenous Community to visit numerous oil and gas facilities in Argentina’s Patagonia region, including Argentina’s new Vaca Muerta non-conventional oil and gas play, where new fracking operations have recently gotten underway. Other sites visited included fracking and gas processing facilities in fruit production areas at Allen, Neuquen in Patagonia, as well as refinery installations in the port area of the country capital, Buenos Aires. In one case at the local town of Vista Alegre (near the provincial capital of Neuquen) the toxic plume emanating from a gas processing plant operated by PECOM (Perez Companc) extended well over two kilometers and headed directly to populated areas. Toxic emissions from oil and gas operations include methane (a potent green house gas) as well as Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) which can cause severe health complications, cancer and in some extreme cases, sudden death. [link to all restored videos: http://bit.ly/CEPArgentina]

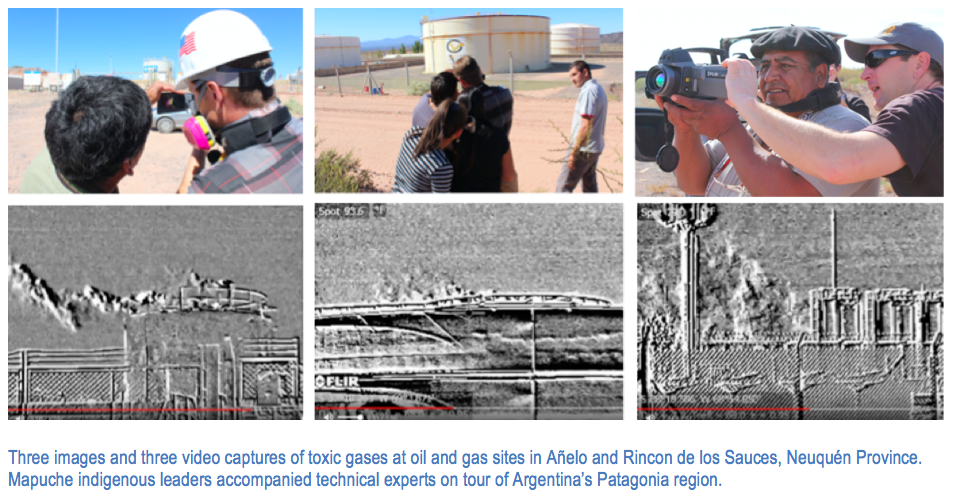

Accompanied by the Center for Human Rights and Environment (CHRE/CEDHA), founded by Argentina’s former federal Environment Secretary, Romina Picolotti, and invited by the Mapuche Confederation of Neuquen, technical experts from the organization Earthworks, visited Argentina with the objetive of measuring gaseous emissions from the country’s oil and gas sector. Specifically, the team looked at toxic emissions that could put the health and lives of workers and local communities living in the vicinity of oil and gas sites.

VOCs emissions are typical residual emissions from oil and gas operations, and should be carefully controlled. They can be instantaneously deadly if inhaled suddenly and in large quantities. They are also cancer-causing if exposure is maintained over longer periods. Methane gas, which is also a typically leaked gas from standard operations in the sector, is also a climate change causing agent as it is up to a hundred times more contaminating for the atmosphere than CO2.

The experts were invited by the Mapuche Indigenous community and visited Añelo, the site of Vaca Muerta–where a recent major non-conventional oil and gas reserve (for fracking) was identified and where exploration and production are already underway. The team also visited Rincon de los Sauces (near wine producing Mendoza Province) and where the oil and gas sector has been active for a number of decades.

The technical team also toured several oil and gas sites where gas and oil is extracted or processed, in the vicinity of the city of the provincial capital of Neuquen–in Patagonia (accompanied by the organization OPSur), Allen (particularly known for fruit production, where local community members accompanied the group) and Dock Sud, a petroleum and gas refinery area in the national capital of Buenos Aires.

Some of the companies that were visited and controlled for fugitive emissions leaks, included YPF (the state-owned enterprise), Petrobras (of Brazilian origin), Chevron, Oldelval, Plus Petrol, Pampa Energia, Dapsa and Pecom. In nearly all sites visited (more than 25), fugitive emissions were registered emanating from a variety of oil and gas installations (wells, separators, compressors, pumps, storage tanks, chimneys, and trucks, among others).

What most worries the technical team that carried out the emissions video registering and that later offered a one-day workshop to indigenous leaders and environmental groups in Neuquen Province to share the images and data collected is that the fugitive emissions are completely invisible to the naked eye. If you are standing next to the facilities you don’t see any type of smoke but when looked at through the camera’s view finder, the contamination is alarming.

Pete Dronkers, Earthworks’ certified thermographer said, “The infrared camera we used to reveal this normally invisible oil and gas air pollution is also used by regulators and companies in the U.S. for the same purpose.” He continued, “People exposed to the volatile organic compound pollution we detected can experience negative long and short term health consequences, including cancer. That’s part of the reason why former US President Obama implemented new rules to limit this type of pollution. Rules now-President Trump are trying to kill, although unsuccessfully to date.”

The camera utilized by the experts is a FLIR GF320, valued at over US$100,000. It is commonly utilized by the industry to monitor fugitive leaks of methane, VOC and other toxic gases. In contrast to other infrared cameras which only register heat, the FLIR is carefully calibrated to capture a wide spectrum of gases, including benzene, butane, ethyl benzene, methane, propane, octane, toluene, and xylene. The camera users are especially trained and certified not only to handle the camera, but to interpret the images and data collected. The Earthworks team that visited Argentina regularly conducts spontaneous site checks throughout the United States, and informs communities of their findings and the data collected. They also approach regulatory agencies with their findings and offer legal testimony in cases brought to justice for contamination. As certified operators, their work and opinion are legally admissible in court.

Jorge Daniel Taillant, Director of the Center for Human Rights and Environment (CHRE/CEDHA), who organized the tour for the Earthworks team commented, “what we have seen here is that while it’s fairly simple for companies to control these toxic emissions, they have no intention or incentive, nor the political pressure from regulatory agencies, to do so. They should be installing filters, separating and recuperating these gases to avoid impacts to the environment and to local communities. We have approached the oil and gas sector about these emissions. A while back I spoke to the director of the state oil company YPF’s leading research agency (YTEC) and asked him if they were working on ways to avoid and capture fugitive methane leaks in the industry. His response was simply, ‘what fugitive methane?” Nearly all of the more than 25 sites visited by the Earthworks/CHRE visit registered significant leakages.

“On the one hand”, says Taillant, “this response by the YTEC director reflects a lack of interest from the sector to recognize the impacts that they are generating on the environment and on communities. Thy are not even interested in recuperating lost product, which at the end of the day is a loss of income. Solving the problem is generally easily achieved and does not generate significant costs, in fact, they can recuperate the investment of retrofitting their equipment to avoid leakage, and even make a profit by doing it. However, what is most important is that the industry stop contaminating the environment and communities. These fugitive leaks are highly toxic for workers at the sites and also for people living downwind from extraction and production.”

During the tour, the visiting team met with local communities, including Mapuche tribes in the Añelo (where fracking is underway) and Rincon de los Sauces (traditional oil and gas production) vicinities. The team even had a chance to meet with some oil and gas site staff who approached the team while filming and was curious about the images captured. Workers present and residents living near Argentina’s oil and gas facilities regularly complain of foul odors coming from production sites. Some complain of eye irritation, skin rashes, headaches and sleeping disorders, which they presume has to do with the impacts of the oil and gas sector.

“Communities, whether they’re in Argentina, the U.S., or anywhere else, shouldn’t have to pay with their health so that oil and gas companies can make a bigger profit,” said Earthworks organizer Priscilla Villa who was also on the Argentine tour. She continued, “Unfortunately our infrared videos show that, in Argentina and in the U.S., that’s exactly what’s occurring. We hope communities everywhere will use these videos to embarrass companies into cleaning up, and to force governments to do their jobs and protect their own citizens.”

The chief Lonko for the Mapuche in Rincon de los Sauces, Faustino Molina, accompanied the technical experts on the tour through his tribal lands, where numerous oil and gas facilities have been operating for the past several decades. He was taken aback by the FLIR camera images, surprised to see the extent of the contamination but not surprised to know that there was contamination. He suggests that ever since the sector arrived to Rincon de los Sauces, he and his family have suffered all types of ailments, from eye irritation, to rashes, to headaches and sleeping problems. He has also seen his livestock dwindle as well as the deterioration of flora in the vicinity.

It was Earthworks’ first visit to Argentina, but they have been carrying out similar visits and emissions image registering for hundreds of sites in the United States. They approach local communities with their findings and explain the risks and impacts they are likely to suffer due to the futile gas emissions to which they are being exposed. They also approach companies and state regulatory agencies to press for measures to avoid these impacts to people and to the environment.

Romina Picolotti, former Secretary of Environment of Argentina (from 2006 to 2008) and founder of CHRE/CEDHA, who organized the tour, intervened in the oil and gas sector when she led Argentina’s federal environment agency (the equivalent of the US’s EPA). She commented on the findings of this site visit, “What is most essential is invisible to our eyes. Registering these emissions is a first step. the next is to capture these gases to avoid their impacts to people and to the environment. This is possible by obliging companies to install filters and separation devices. There is no excuse for not acting immediately with this undeniable evidence. The oil and gas sector systematically denies that it contaminates, but these emissions are clearly intentional. They know what they are emitting, the crude emissions are in the very design of the equipment. We can see that the storage tanks do not have filters or systems to capture or separate these toxic gases. They use the atmosphere as a gas waste dump, with very series impacts to our environment and to our communities. The irresponsibility with which these companies operate parallel the enormous impunity granted to them. When I was Environment Secretary, we chose to order a full closure of Shell’s refinery in Buenos Aires, for reiterative violations of Argentina’s environmental law. Ironically, Shell’s CEO at the time, José Aranguren, is now Argentina’s Energy Minister.”

Link to all of the registered videos of toxic emissions: http://bit.ly/CEPArgentina

For more information:

Jorge Daniel Taillant

+1 415 713 2309

[email protected]